THE SINKING OF THE AFRIDI

The First ‘Dunkirk‘: the Norwegian Campaign April/May 1940

John Gritten was on HMS Afridi – the Royal Navy’s largest destroyer and the last ship to leave Namsos during the evacuation – when it was bombed and sunk on 3 May 1940.

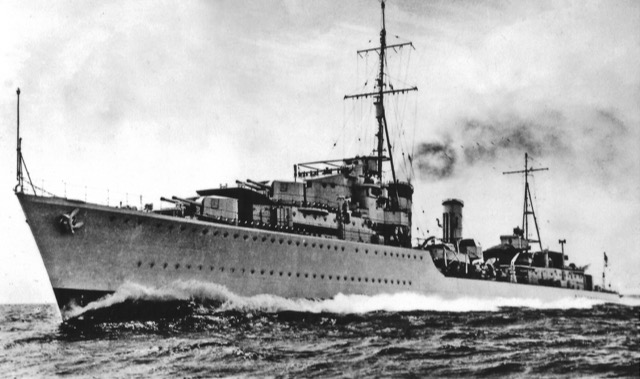

HMS Afridi, the Royal Navy’s largest destroyer. John Gritten was onboard when it was bombed and sunk in Norwegian waters on 3 May 1940.

Afridi survivors

Ill equipped and with no air cover, the Allied expeditionary force was doomed and the decision was made in London and Paris to withdraw the 12,000 troops from Central Norway.

Aged 20, John Gritten was the Royal’s Navy’s first conscript of World War II. He was drafted in the Royal Navy Special Reserve and given No. 1 as his Official Number. In return, he was expected to get coverage in the Daily Mail for what, in media terms, really was the Silent Service. He put pen to paper on the mess table during his first evening of service but what Whitehall might have wanted, officers down the line refused to let him file. John promptly opted to be a stoker ‘rather than pound a typewriter’.

Extracts from John’s war memoir FULL CIRCLE. Log of the Navy’s No. 1 Conscript:

Radio-Telegraphist Jean Raoul aboard the French destroyer Tartu intercepted the last messages from Afridi, that she was running out of ammunition, that she has been hit and was going down.

I had just turned the valves of No. 6 and No. 8 sprayers at the side of the furnace front when there was a sudden tilt to starboard. We were making a very tight right turn. Then in quick succession came two dull detonations that made the plates shudder. Simultaneously, the lights went out. Sam leaped across the boiler room and up the ladder, disappearing into the darkness above. There was a metallic clang as he closed the airlock behind him.

In the darkness I groped and fumbled with the sprayer valves: I had to twist them anti-clockwise to turn them on. I slithered like a boxer in the ring from one side to the other, manipulating the sprayers, pushing the flaps in and out haphazardly, hoping they corresponded with the sprayers I was turning on. Handling sprayers in the dark was not something I was taught in my stoker’s preliminary training.

Suddenly, the airlock door opened far above me, and Sam appeared making urgent beckoning gestures. He shouted down: ‘We’ve been hit. For fuck’s sake come up!’ And as I climbed the ladder, he added: ‘It’s fucking awful up here.’

Between those two bombs both the seamen’s mess-deck (where many of the soldiers and Bison survivors had been) as well as the stokers’ mess-deck were shambles. My 4.7 supply party had been wiped out.

Those who had not been consumed by the fire which started immediately or asphyxiated by the fumes were drowned by the inrush of water. No one in the stokers’ mess could have stand a chance.

After Imperial had come alongside us, telegraphist Bill Outram had an experience which would haunt him for another six decades: ‘In a lower porthole I saw a face I instantly recognized as that of a particular friend of mine. The scuttle of course was secured so I couldn’t hear anything, but my friend kept mouthing what I understood as Help me, Bill! Help me! The signalman who was standing beside me agreed that that was what Jim was pleading. I went down into our empty communications mess-deck and said a prayer for Jim and for all the other men trapped in Afridi.’