JOURNALISM

NOTES FROM MY EARLIEST DIARIES

Diary 1930. (I am 11) Went to Blackhall Rocks with my father and Councillor Turnbull. This place is outside my father’s constituency (see above). It is a grand place of honeycombed cliffs and caves… Go to the “Croft”: a part of the town of Hartlepool composed of fisher people but who have characteristics which are entirely their own. They have yet a different dialect. Afterwards walk along the sea wall dating from the time of Henry VIII (1509 – 1547).

Diary 1931. (I am 12) Went to the Houses of Parliament with Daddy who was showing constituents around. Went to a grand hotel with Daddy, where Lord Rothermere has a suite. After waiting in an ante-chamber, while Daddy was talking with the “great man” inside, I was called in. He was a tall man and after saying the usual “pleasantries” he took from his pocket a “fiver” which he handed to me, with the inconsequent air of a man who has been constantly wealthy… Mother and I go to Turners in Shepherds Bush market and get a bicycle. It is a lovely one with pneumatic tyres. Thank you Lord Rothermere!

I hear a cuckoo for the first time this year.

Wrote to Lloyd George expressing my gladness at his recovery from his illness.

Daddy goes to the Hartlepools to fight an election. Historical General Election. Clean fight between Daddy and a socialist MacGregor by name. Daddy gets in with big majority. The National Government is to be led by Mr Ramsay MacDonald. Our member for North Kensington, Duncan, was shot at and had his car overturned. Daddy comes home.

Diary 1932. (I am 13) Went in Ladbroke Square after tea with Arthur and Faith. He picks up a torn up letter. We piece it together and find it is written by a lover!

Diary 1933. (I am 14) My birthday. Daddy takes me to dinner at the House of Commons at night. I enter for the Common Entrance examination at St Paul’s School… Instone and Geffen tried for C.E. at Westminster but as they are both Jews, and the school only allows 1 Jew in a year, it is only Instone that passes.

Mr Gill takes a few of us to the War Museum. Very interesting. A week later I go to the War Museum by myself, in order to see those things which I did not last Saturday.

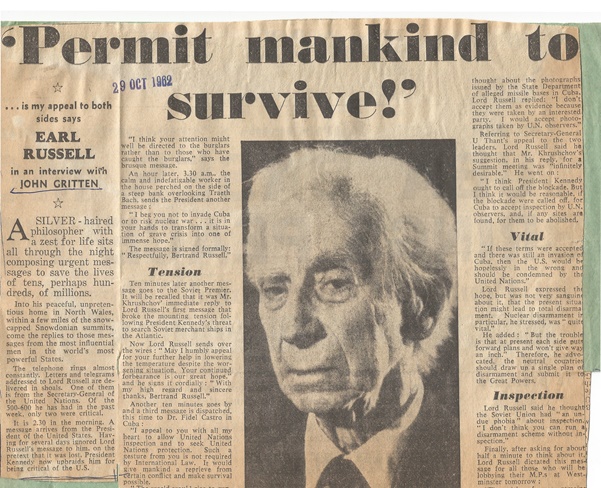

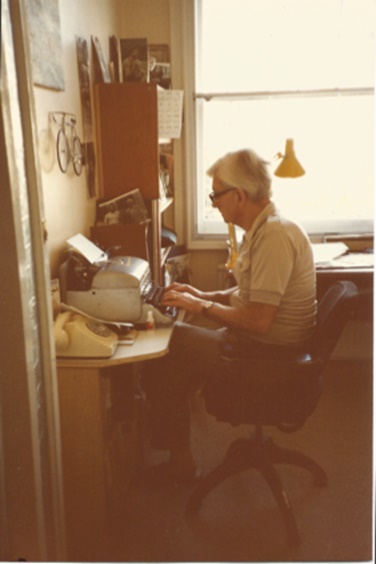

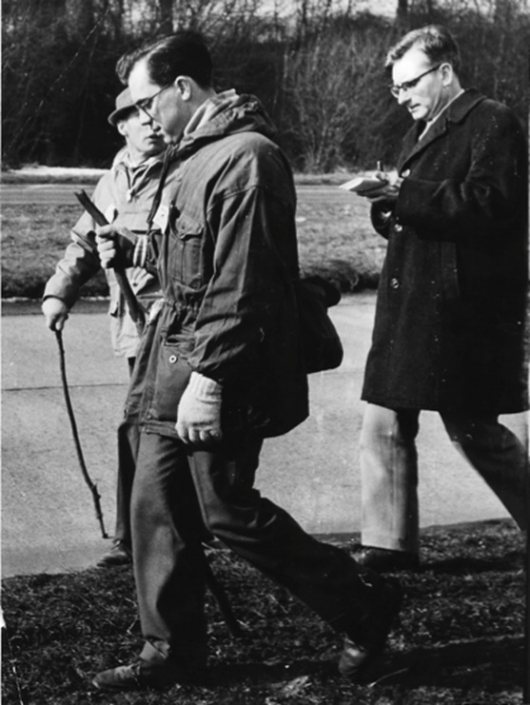

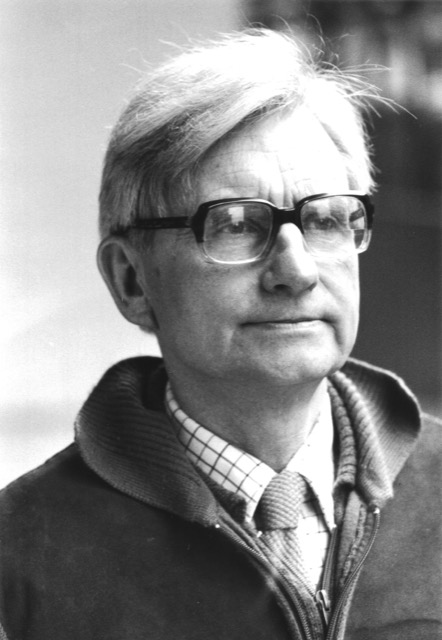

My fifty-six years as a working journalist got off from a shaky start. The first seven months of apprenticeship, abruptly curtailed by National Service, were the most frustrating in a life that has otherwise been psychologically rewarding. I started as a trainee news reporter on the Daily Mail in January 1939. This was virtually fixed by the ‘old boy network’: between my father and Lord Rothermere. There was no more Right-wing national newspaper than the Daily Mail whose proprietor for a time embraced the British Union of Fascists. When Lord Londonderry learned that his godson had embarked on a career in journalism he wrote to my father: ‘I only hope that his strong character will not be destroyed by the dangerous influences of the Press’. What he could never have envisaged, is that the influence that launched me in a definite Leftward direction did actually come from within the paper.

My first story was about Chitty-Chitty-Bang-Bang, the original racing car with a Zeppelin engine, which was up for sale – that won me my first Daily Mail by-line. The second was an interview with a Swiss schoolmaster who had won fame with his 10,000-mile ride from Buenos Aires to New York on two horses – that earned me a postcard with ‘Congratulations! A very good job you made of it’.

In May 1939 under the headline 7,000 HUSBANDS ARE ‘TWENTIES’ I had written about the Armed Forces Act which had just been passed in Parliament, introducing conscription in the UK for the first time in peacetime. Three months later I was informed that I was to serve in the newly formed Royal Navy Special Reserve. I was 20.

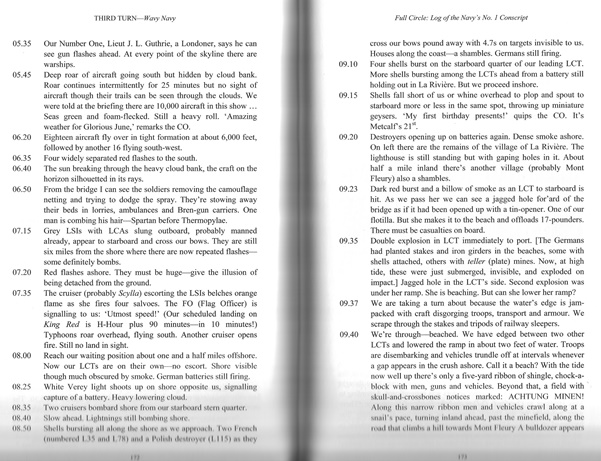

During the war, John Gritten fulfilled his appointment as an Official Naval Reporter for the Admiralty’s Press Division. He was the only ONR to be in a craft that beached in Normandy on D-Day.

Our craft got clear, but, when well-off-shore, began to take in water rapidly. Her bottom had been ripped by one or more of the thousands of beach obstacles…The tide receded a long way, to reveal an amazing sight on the beaches. Thousands of rusted iron-girders bolted together in threes like stacked rifles, had been driven into the clay and sand. Their jagged edges at high tide either barely protruded above the water, or, more often, were just submerged. How so few craft had sustained really serious damage, was a miracle…wooden stakes were driven into the beach to which shells, mines, and other under-water booby-traps, had been attached.

At low-tide Naval beach parties co-operated with Army sappers to remove as many of these obstacles as possible, before the next wave of craft came in. All afternoon, there were shattering explosions and shrapnel hummed through the air and cluttered against the craft left high and dry on the beaches, as the parties touched the mines. Bulldozers and mobile cranes worked ceaselessly, tearing away the iron-girders and stakes.

Not till after dark, did the Luftwaffe put in an appearance. Then, a few planes, operating singly, passed over the fleet waiting off-shore, and were met by a terrific barrage. Red, green and yellow tracers cascaded into the sky, and vivid orange flashes stabbed the darkness. The Navy let loose everything it had in the way of ack-ack, and not a ship was hit.

From the report written in the Admiralty on his return from Normandie

Production and managing editor of three London-based African news magazines: New African, Africa Now, Africa Today 1977 – 1997.

Correspondent for French, Swedish, Romanian and Bulgarian newspapers and magazines.

A Storm in a Teacup

La Marseillaise 20 December 1954

As happens sometimes, on these foggy December mornings, Mr Smith discovers in his newspaper, propped up right before his eyes against the teapot, that the unfortunate Continent is once again cut off from England. The news provokes a silent groan of sympathy between two mouthfuls of porridge. Certainly, it provokes neither disquiet nor regret: insularity is the endemic condition of all islanders. But when Mr Smith learns from the adjacent column that the contents of the teapot are under threat, he abandons his legendary phlegm and his face is suffused with undisguised consternation. One of his friends was so affected the other morning by the announcement that the price of tea had gone up for the sixth time this year that he got up from the table in silence, leaving untouched on his plate, his egg and bacon . . .